15th Century | 16th Century | 17th Century | 18th Century | 19th Century | 20th Century | 21st Century

The building which now houses the All Souls College Library was constructed in the eighteenth century principally with money donated for that purpose by Christopher Codrington. His wealth chiefly derived from plantations in the West Indies which were worked by enslaved people of African descent. For the next three centuries the Library was known as the Codrington Library. In 2020 the College decided to cease referring to the College Library by that name in order to make plain its abhorrence of slavery.

The origins of the Library predate its effective refoundation in the eighteenth century by some three centuries.

Fifteenth Century

Henry Chichele, Archbishop of Canterbury, the co-Founder of All Souls College (with King Henry VI) in 1438, decided that the College should have books and a library from the very outset. In its first years, the College set about accumulating a good all-around working collection for those working in the higher faculties of theology, law, and medicine, although the Statutes envisaged that Fellows would study only arts, philosophy, theology, and law. Other subjects came also to be represented through donation and acquisition, among them the history of England and Italian humanism.

Fellows of the College left books to the Library from the very beginning: a donor of importance was the bibliophile bishop Dr James Goldwell. By the end of the fifteenth century, the library consisted of about 250 manuscripts and 100 printed books; this number was to increase gradually over the next century through purchases and gifts.

Sixteenth Century

Unlike the Chapel, which lost its organ, reredos, and service books during the turmoil of the Reformation, the Library emerged more or less unscathed, and under Elizabeth I found a new champion in the form of Warden Robert Hovenden (1574-1614).

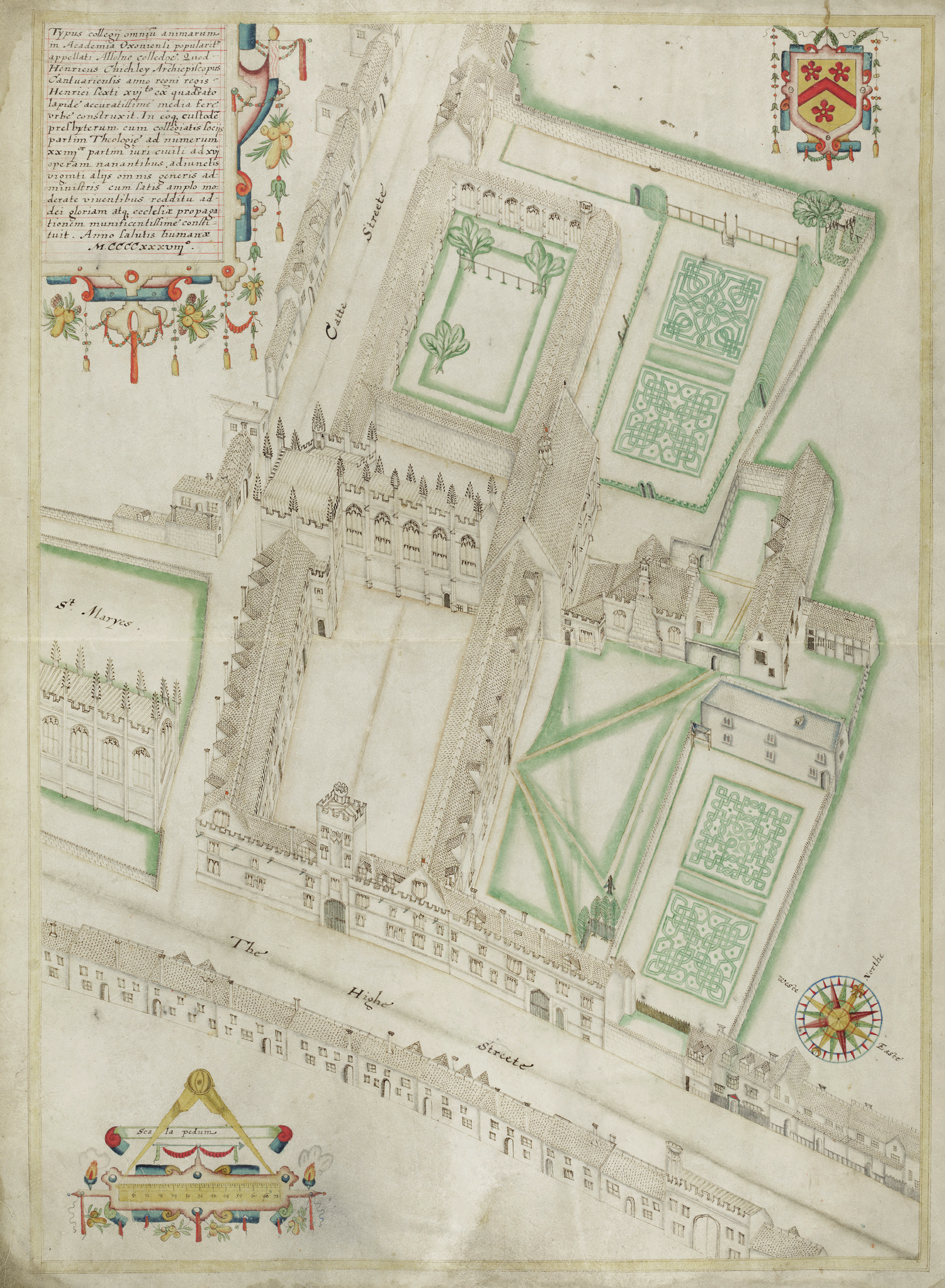

He drew up a new catalogue in 1575, erected the beautiful plaster barrel ceiling in what is now the Old Library, introduced more capacious book presses, and commissioned a full set of maps of the College’s estates.

During his Wardenship, the College acquired books through gifts in lieu of monies from tenants: this accounts for the first fine binding known to come into the College’s possession.

The Seventeenth Century

During the seventeenth century, the College continued both to buy books and to receive donations from Fellows, of which the most substantial was that of Dudley Digges, who bequeathed over a thousand books and pamphlets, including English literature. These and other additions made the shortage of space yet more acute.

The Eighteenth Century

This was solved by a substantial legacy of £10,000 received by the College in 1710 from Christopher Codrington, sometime Fellow and governor general of the Leeward Islands. His family wealth principally derived from sugar plantations — worked by slaves — in Antigua and Barbados. Codrington bequeathed his own library of 12,000 volumes to the College, and stipulated that £4,000 of his bequest should be used for the purchase of books. The remaining sum was for the construction of a new library, whose buildings, designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor, were erected between 1716 and 1720; but it was to take until 1751 for the interior to be fully furbished and ready to accommodate books. Codrington, whose wealth at death exceeded £80,000, also left a bequest which established Codrington College in Barbados.

In 1751 a Library Committee was set up, and a new vision of the Library emerged, in which it retained its ancient specialisations in law and theology, and developed its holdings in the classics, history, travel and topography, belles-lettres, and natural history. It came thereby to resemble more a gentleman’s reference library than that of a College. William Blackstone (Fellow 1743-62), the great Common Lawyer who was also a keen student of architecture, probably caused the College to purchase nearly five hundred drawings from the office of Christopher Wren (Fellow 1653-61) in 1751, as well as other rare publications on the subject of architecture.

Armed with the best reference books on historical bibliography of the day, the Library Committee set about acquiring monuments of early printing, both English and foreign. Notable donations came from other Fellows: Ralph Freman in 1774, and, in 1786, Luttrell Wynne, who had inherited his great uncle’s fine collection of manuscripts and books. Around this time Dr Daniel Lysons donated the so-called ‘Amesbury Psalter’, the College’s finest medieval manuscript.

Purchases included ‘modern’ European literary classics, in the most sumptuous editions, and natural history.

The Nineteenth Century

From the beginning of the nineteenth century, however, the Library fund dwindled in size, and fewer books were purchased; in compensation, some donations of note were received from Fellows: seventeenth and eighteenth century Spanish books from P.F.Hony, and Persian manuscripts from Mrs Heber, the widow of Reginald Heber, sometime Fellow and Bishop of Calcutta. These donations added to the diversity of the collections.

The College was roused from a period of quiescence by the Royal Commission of the 1850s, and by the energetic figure of Warden Anson (1867-1914). In his time, a new reading room was built for use by all members of the University, and opened in 1867; the specialisation in law and history was reasserted, and the Library supplied with works relating to current politics and public administration. Other notable events include the inventory of the College archives by C. Trice Martin in 1874-7, and several important donations, including the papers of Sir Charles Vaughan, a major source of information about the Peninsular War and the United States of America in the 1820s, J.A.Doyle’s great collection of Americana, and two collections of military history.

The Twentieth Century

These donations once again created problems of space, which were alleviated by the construction of a bookstore in 1909, and its extension in 1952. In more recent times, the greatest bequest has been the collection of neo-Latin poetry and epigraphy of Warden John Sparrow.

By the late 1990s, it became clear that work was required on the fabric of the Library, and the project of rewiring, rebuilding the bookstack, providing controls of temperature and humidity to modern standards, equipping a dedicated space for conservation, and establishing a number of electronic work stations was begun. This was completed in 2002.

The Twenty-First Century

In the second decade of the twenty-first century the College had extensive discussions about the best ways to address Codrington’s legacy, and its origins in money deriving from the slave trade. In 2018 the College put up a plaque ‘In Memory of Those Who Worked in Slavery on the Codrington Plantations in the West Indies’ which stands facing the Catte Street entrance to the Library. At the same time the College made a substantial donation to Codrington College in Barbados, and established three fully funded graduate studentships at Oxford for students from the Caribbean. In 2020 the College decided to cease referring to the Library as ‘The Codrington Library’. Further discussions—about how best to contextualize the statue of Codrington, and about other academic measures to address the legacy and history of slavery—continue.

The collections continue to evolve. As well as being a repository of books and manuscripts which are made available to scholars around the world in physical and (increasingly) in electronic form, the Library remains guardian to a number of other objects: a death mask of Christopher Wren, a pietra dura table, the reading desks and steps commissioned by Blackstone, and memorabilia of T.E. Lawrence. The historic focus of the collection on Military History and Law is being broadened to include global history and the legacies of the Atlantic slave trade.