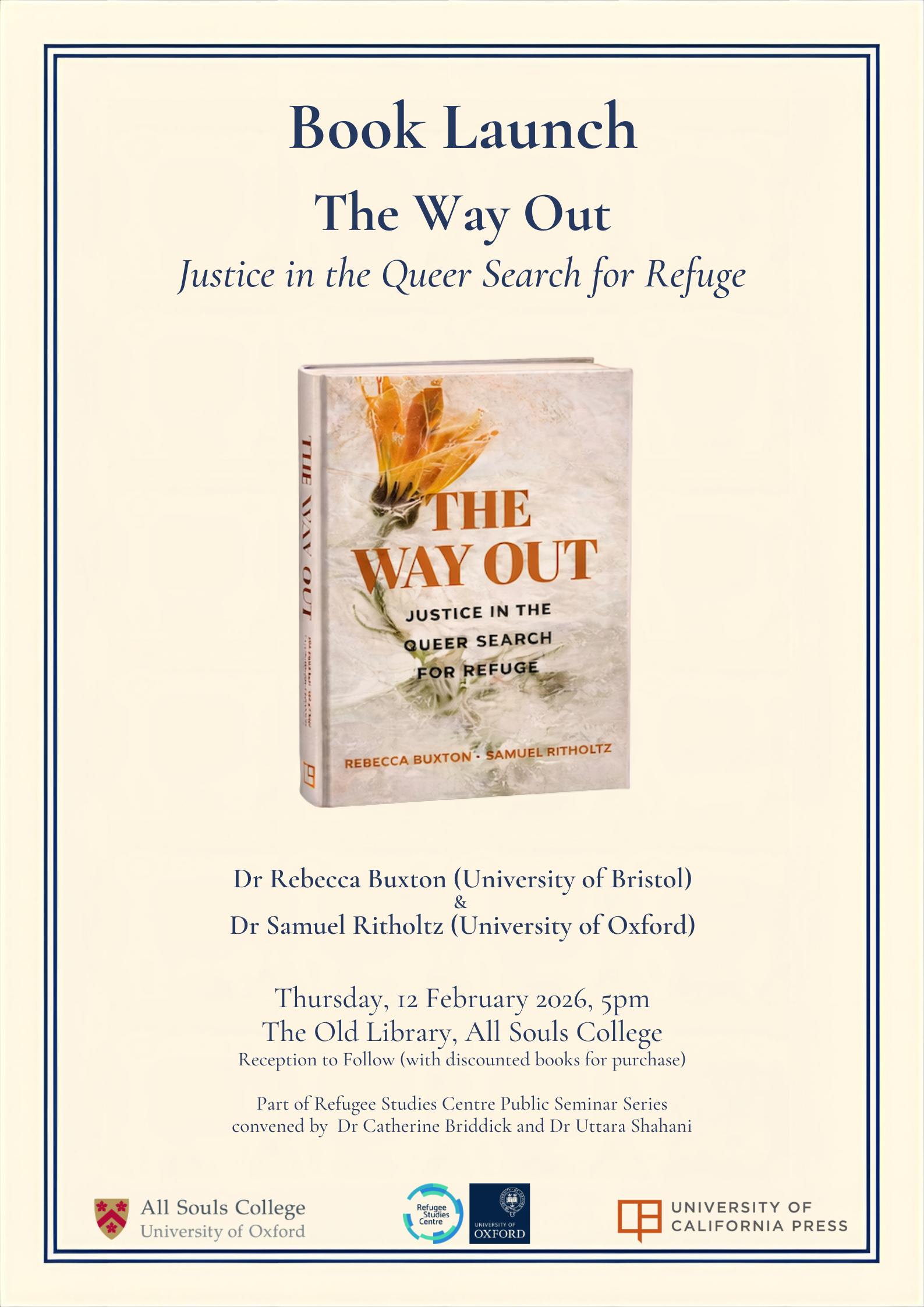

Authors: Dr Rebecca Buxton, University of Bristol, and Dr Samuel Ritholtz, University of Oxford

Location: The Old Library, All Souls College

Followed by a reception with discounted books for purchase

Part of the Refugee Studies Centre Public Seminar Series convened by Dr Catherine Briddick and Dr Uttara Shahani